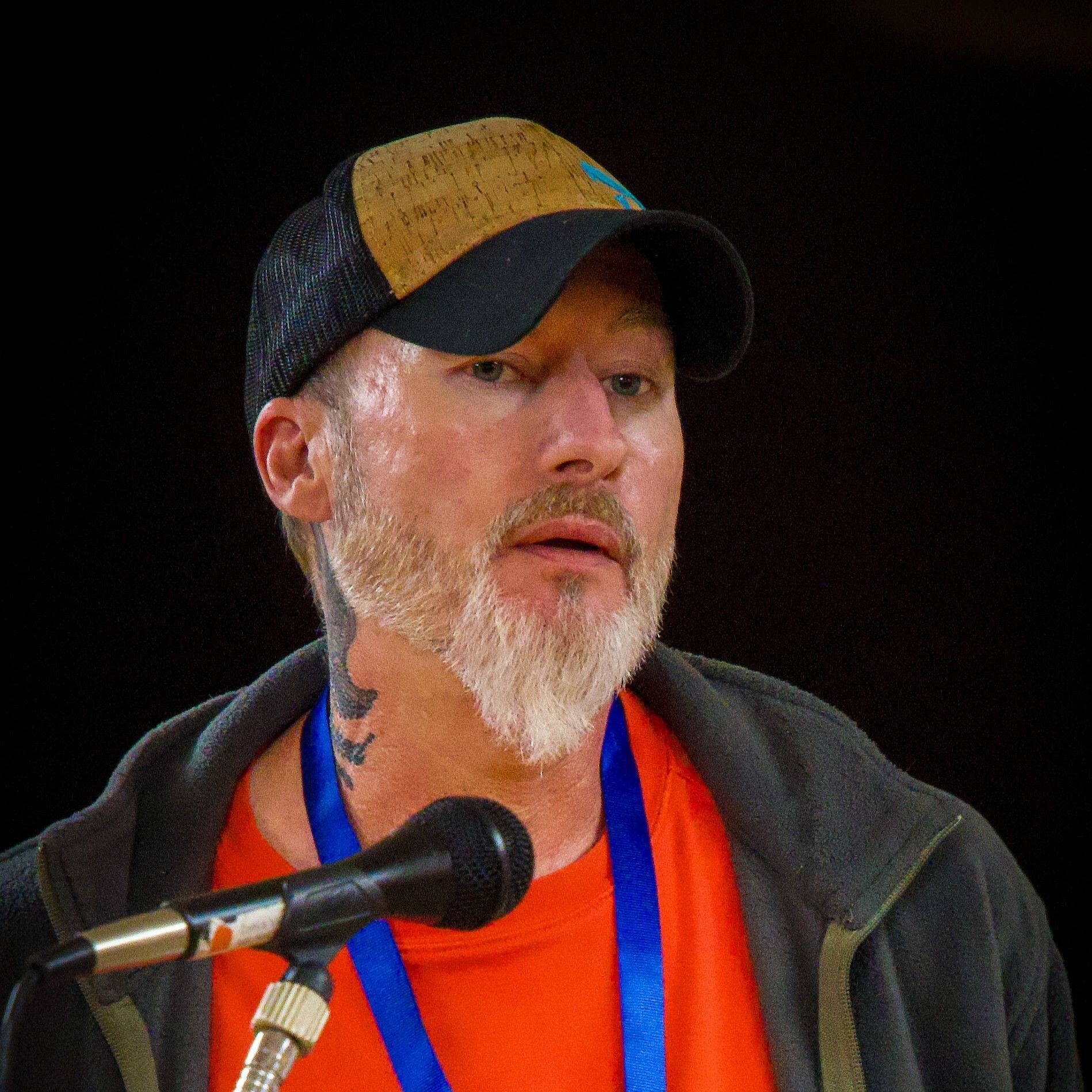

Richard, now an alum of Hartford Dismas House, shared his story with us in October.

I never had problems growing up. I took care of myself, worked hard, and came from a family that expected good grades and college. I did just that, earning an Associate Degree in Criminal Justice.

Soon after, I enlisted in the Army. I became a Sergeant with the Airborne Infantry—first with the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Liberty, then with the 173rd Brigade in Italy.

In 2005 and 2006, I served in Afghanistan. I experienced all that war had to offer. I saw a lot of death, including the oldest and youngest villagers. I also saw what people are capable of.

Our missions were often search-and-rescue or capture-and-kill. Many nights, my team and I would slide down ropes into villages in total darkness to reach our targets. For seven years, I lived by the rules of war and planned to re-enlist.

Instead, I came home carrying physical and emotional wounds: PTSD, 2nd and 3rd degree burns, multiple concussions that caused years of undiagnosed migraines, and nerve damage. Today, after years of advocating for myself with the VA, I’m considered “100 percent service-connected” with total and permanent PTSD. That means the military recognizes me as fully disabled and unable to work.

Life After Service

Within a week of returning home, I was already in rehab for my injuries while trying to readjust to civilian life. Being back didn’t feel real. I carried survivor’s guilt, constantly asking myself: Why did I get to come home?

No one around me could understand that I was used to bombs going off and people being shot—sometimes friends. I couldn’t adjust. I was angry and wanted to return to Afghanistan. I felt like a puzzle piece that no longer fits.

Depression, anxiety, panic attacks, night terrors, and insomnia soon took over. In the Army, no one wants to hear about weakness—complaining ends your career. Alcohol became my cure. It dulled the pain, calmed my anxiety, and helped me sleep. Soon, cocaine followed, so I could drink heavily and still make it to formation.

Even as I re-enlisted and became an Infantry Instructor at Fort Moore, my drinking continued. I thought I had balance, but the nerve damage worsened until I lost all feeling below my knee. My depression deepened. When a colonel told me, “You may never get the feeling back—and your career is over,” I felt abandoned.

Hitting Bottom

After leaving the Army, I moved in with my girlfriend. Drinking consumed me, and after we broke up, I hit rock bottom. I had no drive, no direction, and I attempted suicide.

I spent eight months in a VA hospital, learning about PTSD and substance abuse. But I also left with a new burden: prescriptions. I was given opiates for pain and concussions, and later benzodiazepines. For seven years, I lived in a haze—legally high, just getting by.

For a while, life improved. I met my wife, quit drinking when she became pregnant, and we built a life together. But after our divorce, my world collapsed. She took my daughter, whom I haven’t seen since. She’s turning sixteen this year, and losing her has been the hardest thing I’ve ever faced.

I relapsed into drinking and drugs. The VA took away all my pills, and I spiraled. Despite brief moments of stability—a townhouse, a truck—I was eventually arrested for possession and spent two years homeless. Eventually, I connected with Vet’s Inc. in Bradford, Vermont, a readjustment house for homeless Veterans. I received counseling and therapy, saved money, paid off debt, and bought a car. But my time there ended abruptly, and I landed in prison.

Moving Forward

Today, I’ve been clean and sober for five months. I never want to go back to that side of life again. I still struggle with anxiety and worry, but I’m working closely with the VA on my PTSD, migraines, and substance abuse recovery.

Living at Hartford Dismas House has been key to my progress. Having safe, sober housing helps me readjust. Being surrounded by other residents committed to recovery matters—we each have our own goals, but we push each other forward.

I’m also volunteering with the VA, helping people facing food insecurity. Giving back keeps me grounded. Most importantly, I’m hopeful again. My biggest dream is to reconnect with my daughter and my family. Once I’ve been sober for a year, I want to become a Peer Support Specialist with the VA—because helping others helps me.

For the first time in a long time, I believe that’s possible.